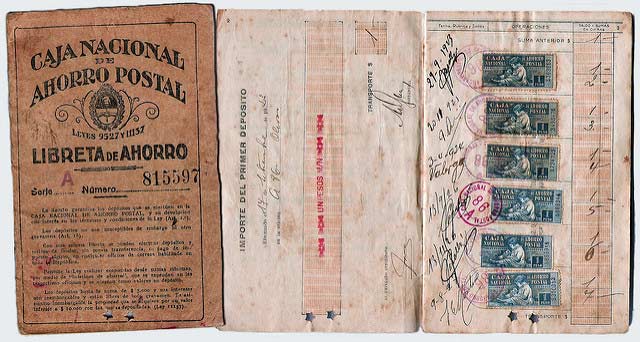

Carolina Lopez learned early in her life a hard lesson about the instability of Argentina’s economy.

It was the late 1960s. She was a grade school student living in rural Northwest Argentina. At the time, post office officials came to her school weekly to sell stamps for a savings notebook in a government program called the Caja Nacional de Ahorro Postal (National Postal Savings Fund).

Lopez, along with thousands of children all over the country, dutifully saved money and purchased stamps of small denominations to put into the savings booklet. Each stamp they purchased represented a deposit in their savings account.

Argentina’s Postal Service Savings program was founded in 1915 by President Victorino de la Plaza with the aim of teaching children the value of saving money. The program promised that the stamps would incur interest and later be redeemable at any post office.

The inside cover of the booklets featured sayings that highlighted the importance of saving money such as,

‘Saving is not being greedy, it is simply preserving what is unnecessary in the present for what may be indispensable in the future.’

“All the children were enthusiastic because they promised us we could receive our money at the end of the year,” says Lopez. “Finally, at the end of the year we went to the post office and they told us, ‘There is nothing in the account.’”

“That memory stuck in my mind,” says Lopez. “Even though I was a child, I thought, ‘How could that be? I put money and now there is none!’ I’m even getting angry thinking about it right now,” she says with a rueful chuckle.

In fact, all the savings accounts that thousands of Argentine children invested into over decades of the program were wiped out, whether to cover the maintenance cost of the program, due to inflation and devaluations, or change of currency. Such is the perpetual state of Argentina’s volatile economy.

Despite failing miserably at its intended purpose, Argentina’s Postal Service Savings program continued until 1994 when it was privatized and converted into an insurance program. At that time, all the accounts were placed into a private bank, Banco Hipotecario.

Many Argentines are probably unaware that their childhood postal savings accounts still exist — on paper at least. If they go to the bank to check the balance however, they will find nothing but a long list of zeros.

Desperate for Dollars

Saving money, only to lose it, is practically an Argentine right of passage.

“We (Argentines) all have a story like this,” says Lopez. In the end, the Postal Service Savings program’s main lesson for young Argentines was: be wary of Argentine banks.

Lack of trust in Argentina’s financial institutions is still so dismal that one half of the country’s adults don’t have a bank account, according to the World Bank.

Over the decades, purchasing U.S. dollars with pesos has become the default method for Argentines wanting to protect the value of their savings, by literally ‘stashing cash under the mattress.’

“It’s not that we want dollars particularly, but just to save what we have worked for,” says Lopez.

Another common tactic for Argentines to conserve the value of their capital in the unstable banking environment is to ‘ahorrar en ladrillos,’ or ‘save in bricks,’ — invest in construction materials to build a house or purchase property.

Argentines who don’t buy dollars or bricks are known to spend their pesos as fast as they earn them. This is because — even in the dearth of an acute economic crisis, Argentina’s inflation is consistently high, meaning that money loses value, even if it’s just sitting in the bank.

The Wild Ride of Argentina’s Financial Crises

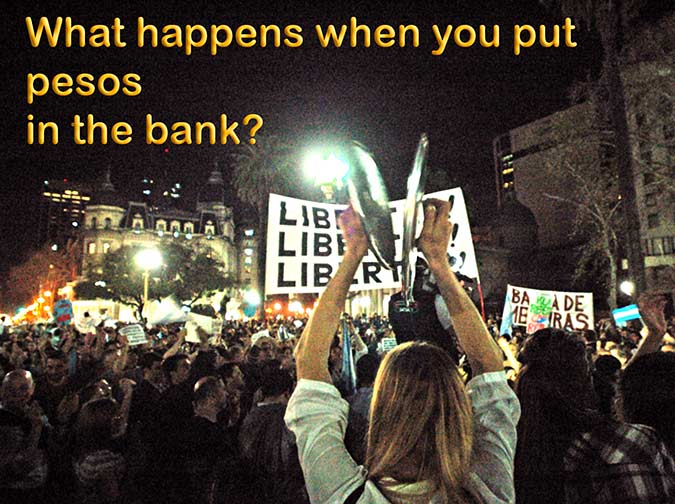

Lopez was also among thousands of others who lost money holding it in an Argentine bank during the 2001 financial crisis. At the time, Argentina was bankrupt and unable to secure foreign loans. The government reacted by imposing a corralito, or bank freeze, right before Christmas, causing huge protests around the Plaza de Mayo and looting throughout the city.

Twenty-four people died in the clashes. In one of many dramatic moments of Argentina’s history, then-president De La Rua declared a state of emergency, resigned a few days later and escaped the Casa Rosada by helicopter.

Since regular citizens could not access their money in the bank, commerce halted. Many Argentines relied on bartering to get their basic needs met. Some neighborhood cooperatives made up little handmade coupons to use as payment for goods and services.

Argentina famously had four presidents during the last two weeks of December 2001, with a fifth being elected on the first day of 2002. The end result of all the chaos for normal citizens was that the peso was depreciated to a fraction of what it was worth before and nearly 60% of the country fell into poverty.

Losing most of the money she had saved through her adult life after the 2001 bank crisis and devaluation, Lopez was haunted by the lesson of her childhood and determined to never make the same mistake.

“We know: ‘never pesos,’” says Lopez. “It doesn’t matter if it’s a Military government, Peronist or Radical (parties) – the same thing always happens. Everything you’ve worked for and saved for just disappears.”

Crisis Currency: Bitcoin to the Rescue in Argentina

Understanding the history of Argentina’s economic volatility makes it obvious why citizens like Lopez would embrace a new way to hold onto their savings without being at the mercy of the perpetual cycle of crisis, inflation and devaluation of the national currency.

Enthusiasm for bitcoin, digital currency created by computer processes called blockchains, boomed in Argentina during the years of 2011-2015, when the country was once again in the midst of another financial crisis.

At that time, the country defaulted on foreign debt that had been taken over by so-called ‘vulture funds.’ The government responded by taking the unusual step of restricting the use of foreign currency and fixing the exchange rate so that it was highly favorable to the peso.

The currency restrictions, commonly known as the ‘cepo bancario’ meant that any money coming into the country through authorized channels had to be converted to pesos at the official bank rate, which was valued between 30-45% lower than the black-market rate that emerged. The parallel black-market rate, which came to be referred to as the ‘dólar blue’ (Blue Dollar) was commonly considered to represent the true value of the Argentine peso. This made the Argentine peso a pariah currency worldwide. Travelers to Argentina would be surprised to find that, once back home, their banks refused to exchange pesos back to another currency.

The ‘Blue Dollar’ parallel currency market, (which is now the Blue Dolar is back and stronger than ever after a change of government) while technically illegal, operates in the open with only occasional raids by AFIP, Argentine tax officials.

The cries of “cambio, cambio — dolars, euros” have become part of the landscape of Buenos Aires’ downtown streets and many family stores operated exchanges in their backrooms throughout the city.

Only those with access to dollars or Euros in cash could get the favorable black-market rate though, which left most Argentines out of the arbitrage game. Desperate to get their hands on dollars, some people in Buenos Aires took trips over to Colonia, Uruguay, where bank machines gave out U.S. dollars in small amounts. Often the day trippers would travel with not only their own bank cards but those of friends and family who had enlisted them to withdraw the U.S.$200 daily limit from the bank machine on their behalf.

Ryan Drift, an American and early-adopter of bitcoin who lived in Buenos Aires during the era of the parallel currency market was one of a handful of foreigners who was able to enjoy a nice lifestyle buying and selling bitcoins. As a bitcoin advocate he eagerly helped local friends get around the currency restrictions by teaching them about cryptocurrency.

Indeed, compared to taking a boat trip to another country just to get a small amount of dollars to save, cryptocurrency suddenly didn’t seem so complicated, especially for those working in the tech sector.

Some even went further, moving on to ‘mining’ bitcoin on their home computers. To mine bitcoin people use their computer power to solve complex problems that produce more bitcoins.

Thanks to Argentina’s cheap subsidized electricity rates, mining for bitcoin turned out to be very profitable for those in the country who did so early on.

Unlike more stable countries where bitcoin and other crypto currencies were — and still are — considered to be more a novelty for speculators, in Argentina its utility was undeniable. Bitcoin enabled people to get around government regulations and receive payments from outside the country, without a loss of forty to fifty percent of its value.

Among those who hopped on the opportunity was an Argentine startup called Bitpagos, founded by Sebastián Serrano, which enabled businesses and individuals paid with foreign funds to circumvent the currency restrictions by converting foreign payments to bitcoin and then into pesos at the more favorable ‘blue dollar’ rate.

Since its founding, Bitpagos has received U.S. funding, rebranded as Ripio and expanded throughout Latin America.

Buenos Aires: Latin America’s Capital of Crypto

Today Buenos Aires remains the unofficial capital of Bitcoin in Latin America with nearly 150 companies that accept the cryptocurrency in the metro area.

Among businesses that take payment in bitcoin are a few pubs, a taxi company, some franchises of the American sandwich chain Subway, a coffee shop near the Colón Theater called Bitcoffee, a law firm and even a psychotherapist.

In 2015 Buenos Aires hosted the first bitcoin forum in Latin America.

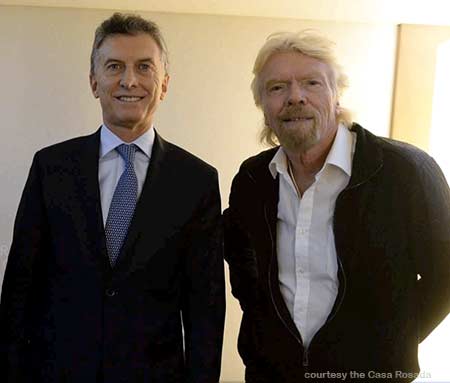

Former president, Mauricio Macri, who was then the opposition mayor, provided city sponsorship of the forum.

Argentina’s embrace of new monetary technology differs from other Latin American countries such as Ecuador, Bolivia and Venezuela, who have tried to ban the use of cryptocurrencies (although Venezuela recently launched a government-backed cryptocurrency called the petro, or petromoneda).

After Macri was elected president in late 2015, one of his first moves as the leader of the nation was to lift the cepo bancario and float the pesos which served to ‘normalize’ Argentina’s currency situation. With the move, the black market for dollars became a tiny fraction of what it was with the currency restrictions under the previous administration of Cristina Kirchner. Now that the Peronists are back in power and Kirchner is once again in office, this time as Argentina’s vice president, things are back to the way they were before.

During the Macri years when the economy was more stabilized, some wondered if Argentina’s enthusiasm for bitcoin — used mostly to get around the previous currency restrictions — would wane.

It didn’t — even in spite of bitcoin’s own volatility.

“Traditional banking is still difficult and it’s faster and cheaper to do a bitcoin transaction — even with the higher fees that bitcoin users have been experiencing lately,” says Franco Amati, cofounder of Bitcoin Argentina, one of the organizations that make up the Espacio Bitcoin community center, known as ‘The Bitcoin Embassy.’

Amati says bitcoin is now used by locals mostly to transfer money outside of the country and increasingly as a speculative investment.

But, he adds that Argentina’s economic turbulence and the population’s distrust of banks has meant interest in bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies will continue.

“It’s because of the things that we’ve lived through — the bank freeze. In ‘89 or ‘90 there was Plan Bondex (another failed government investment scheme), then there was the Austral (a new currency that was used between 1985-1991). It’s one bad memory after the other,” he says. And considering what has happened in the past, he adds, “It helps that it can’t be confiscated (by the government).”

While ex President Macri took an interest in bitcoin, he was less enthusiastic about new technology that may disrupt local labor markets. In 2017, he clamped down on the ride share app Uber, outlawing its use and trying to stop Uber’s operations within the country by blocking it from processing locally-issued credit cards. In a twist of fate, bitcoin was used to circumvent Macri’s anti-Uber clamp down. Uber was able to continue to operate using a bitcoin payment system in order to process customer payments without government interference.

Bitcoin investor and venture capitalist Tim Drapper also encouraged the Argentine president to invest in bitcoin technology during a late 2017 visit to the country. At the time he told Infobae “If the local currency implodes, as it once did here, whoever has bitcoins will be fine.”

An anonymous currency that allows people to hide money from the government — especially in a country with some of the highest taxes in the world — logically spooks some legislators, but it also offers the promise of new technology that would enable a streamlining of financial services. Not to mention that Macri had expressed a desire to tax crypto currencies.

Argentina’s most important future’s market ROFEX is also developing plans to offer services for cryptocurrency investors.

It’s evident that Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies allow people to avoid the high fees, bureaucracy and headaches of Argentine banks, but is the gamble of holding a volatile currency worth the risk?

To bitcoin enthusiasts in Argentina the risk is worth it when weighed against the guaranteed 20-30% loss of value due to inflation that pesos incur sitting in the bank.

Now Venezuelans are following Argentina’s lead and in their case finding life-saving value in cryptocurrency. Saddled with worthless Bolivars (the national currency of Venezuela) due to currency controls even more extreme than Argentina during its debt crisis, tech-savvy Venezuelans are mining and trading bitcoin in order to purchase food and medicine and hopefully survive the humanitarian crisis there.

“There are many Venezuelans that come to Espacio Bitcoin because they are already familiar with bitcoin having heard about it in Venezuela,” says Amati.

Ryan Drift has since followed the lead of one of Bitcoin.com’s founders to convert to bitcoin cash, an offshoot of bitcoin that because of its larger blockchain enables less fees and faster transactions.

Amati from Espacio Bitcoin says concern about higher fees and slower speeds of bitcoin transactions since its popularity surged in 2017 should be solved soon.

“It’s going to be better with the lighting network,” he says.

Lightening network is a new ‘second layer’ of technology being put in place that is meant to operate on top of the bitcoin blockchain and speed up transactions.

Lopez, after losing money in Argentine banks a few times in her life, embraced bitcoin enthusiastically, despite a lack of computer savvy.

She sold an apartment in Buenos Aires a few years ago and put all the proceeds in bitcoin — when one bitcoin was worth a mere $200.

Today, thanks to her early and repeated lessons to distrust Argentine banks and willingness to take a risk, the girl who grew up on a farm in rural Argentina is today a bitcoin multimillionaire.

| How to Invest in Bitcoin? |

| •To learn about bitcoin in Buenos Aires people can head to the Bitcoin Argentina Meetup in Buenos Aires, where they can trade bitcoin with other attendees.

|

|

•Espacio Bitcoin, housed in a building known as the ‘Bitcoin Embassy’ has a bitcoin ATM. Anyone with a Blockchain.info account can purchase bitcoins instantaneously (although the fee is a bit high, as with most bitcoin ATM’s). Espacio Bitcoin Cofounder, Franco Amati, recommends those who are interested purchase a little bit at a time to not be so affected by the volatility and to invest long-term as opposed to short-term.

|

| •Users can also purchase bitcoin online through services such as Satoshi Tango and Bitcoin.org

|

| • To start mining bitcoin instantly for free, download the Get Crypto App for your Firefox browser.

⇒ https://getcryptotab.com/242753 Order Cryptocurrency for Beginners: How to Make Money with Cryptocurrency and Succeed |

[…] high profile politicians putting their money in Swiss bank accounts, and then tax havens and even cryptocurrency in recent years. The country almost defaulted in 1982, but instead scrapped everything and created […]